Building USA.gov’s first AI chatbot during government uncertainty

Client: GSA—Public Experience Portfolio | Year: 2025

Current Status: POC completed and handed off; foundation available for future GSA AI initiatives

Role:

Lead UI/UX Product Designer

Team:

Cross-functional coordination with 2 developers, 1 GSA lead (PM), 1 Analytics lead

Tools:

Figma, FigJam, Slack, Trello

Navigation

The Problem:

When 10,000 daily calls overwhelm a system built for humans

Here’s what most people don’t see when they call a government helpline: There’s a shut-off limit.

USA.gov’s contact center operates under contractual obligations—roughly 10,000 calls or chats per day. Once that quota is hit, the contact center option disappears from the site. You literally can’t reach anyone.

And here’s the thing: a huge percentage of those calls are answering questions that already exist on the website. Simple stuff like:

- “How do I check for unclaimed money?”

- “Where can I find government auctions?”

- “What benefits am I eligible for?”

Every simple call that takes up an agent’s time means someone with a complex issue doesn’t get help.

The agents themselves are under constant pressure—contractual obligations require fast, accurate responses. But they’re essentially reading from the site and dealing with:

- Inconsistent answers between agents

- Communication frustrations

- Pressure to perform while researching content in real-time

So the question became: How do we use our customer service agents more effectively while still serving the American people?

The answer: An AI chatbot that could handle the simple, searchable questions—freeing up human agents for the complex cases that actually need expertise.

The Strategic Challenge:

Leading AI innovation during a reduction in force

Here’s the context that made this project particularly challenging: In early 2025, during active government workforce reductions, GSA’s Board of Directors and senior leadership brought me in to lead product design strategy for their first AI chatbot POC.

This was a high-stakes bet on innovation during organizational uncertainty.

GSA was going through significant workforce reductions. Budgets were uncertain. Priorities were shifting. And leadership wanted to explore AI chatbots—a technology that many people associate with replacing human workers.

The optics were… complicated.

My role became more than just designing conversational flows. I had to:

- Navigate stakeholder concerns about AI replacing jobs (when the real goal was augmenting human capability)

- Lead the design strategy for a POC that would prove value without massive investment

- Design for technical constraints (Drupal AI, Ollama) while government tech infrastructure was in flux

- Build something that could be handed off if team structures changed or contracts ended

This wasn’t just a UX challenge—it was a strategic positioning challenge. How do you lead innovation during organizational uncertainty when you’re brought in specifically for that purpose?

Why a POC? Understanding the strategic context

In a stable environment, you might build a full chatbot. But this wasn’t a stable environment.

Senior GSA leaders and the Board of Directors chose a Proof of Concept approach for three strategic reasons:

- Lower risk during budget uncertainty → A POC requires less investment and can be paused if priorities shift

- Faster time to value → Prove the concept works before committing to full-scale development

- Built-in learning → Real user behavior would inform the next phase rather than designing in a vacuum

But here’s the thing about POCs: You still need to design them like they’re real.

If the POC feels half-baked, stakeholders won’t see the vision. If it’s too polished, you’ve over-invested.

My role: Lead the product design strategy that would make this POC compelling enough to prove viability—demonstrating what was possible without over-engineering for scale we didn’t have yet.

Strategic decision #1:

Which problems to solve first

We couldn’t build everything. With a two-month timeline and a small team, I had to prioritize ruthlessly.

The tension: GSA has hundreds of services. The contact center fields questions about everything from tax forms to disaster relief. Where do you even start?

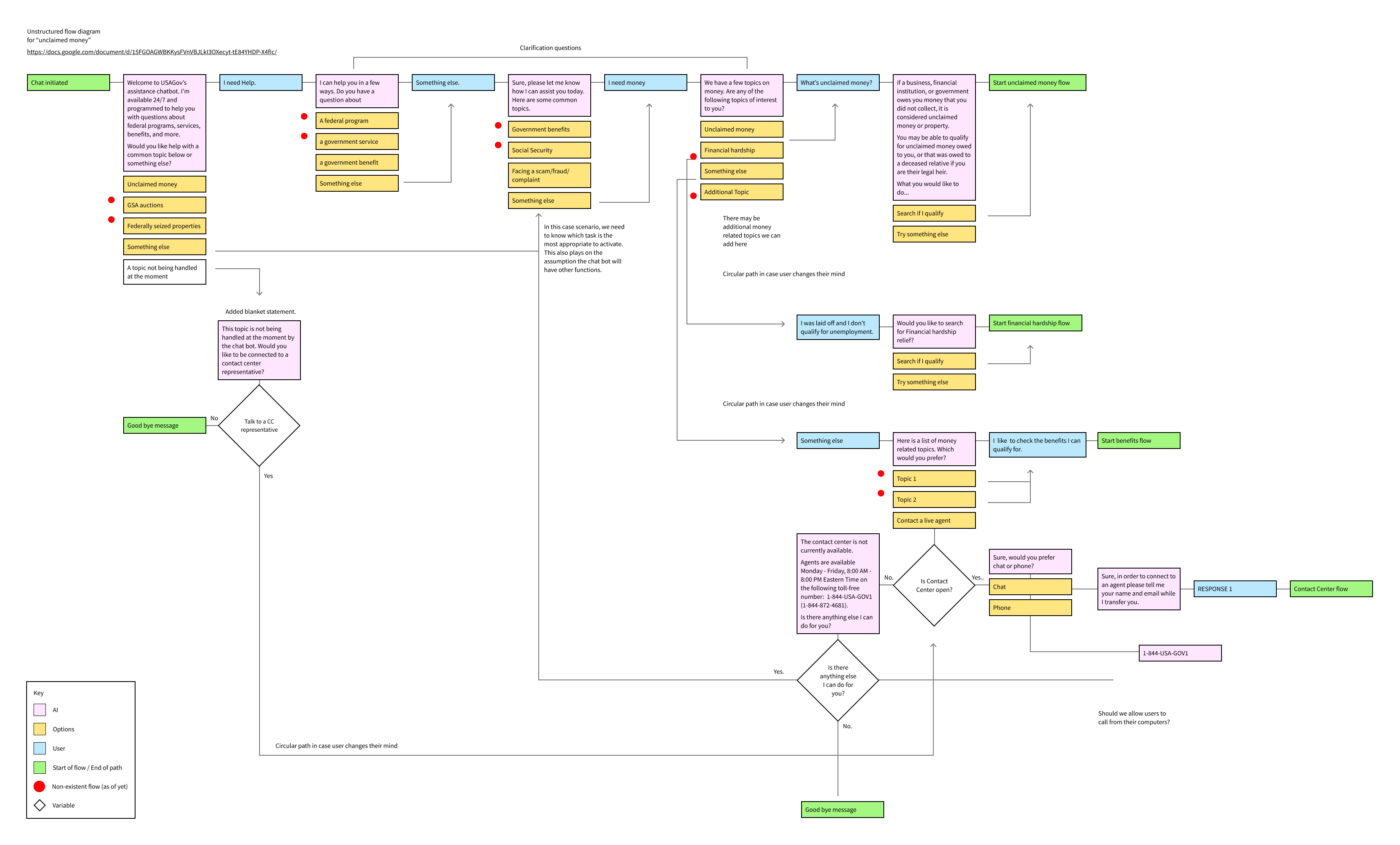

My approach: I analyzed contact center data in Medallia with my team to identify:

- High-volume, low-complexity queries → Questions that agents could answer in under 2 minutes and were GSA-specific

- Clear, factual content → Topics where AI could reliably pull from existing USA.gov pages

- Measurable impact → Queries frequent enough that solving them would meaningfully reduce volume

- Domain ownership → Content that GSA directly controlled and could iterate on

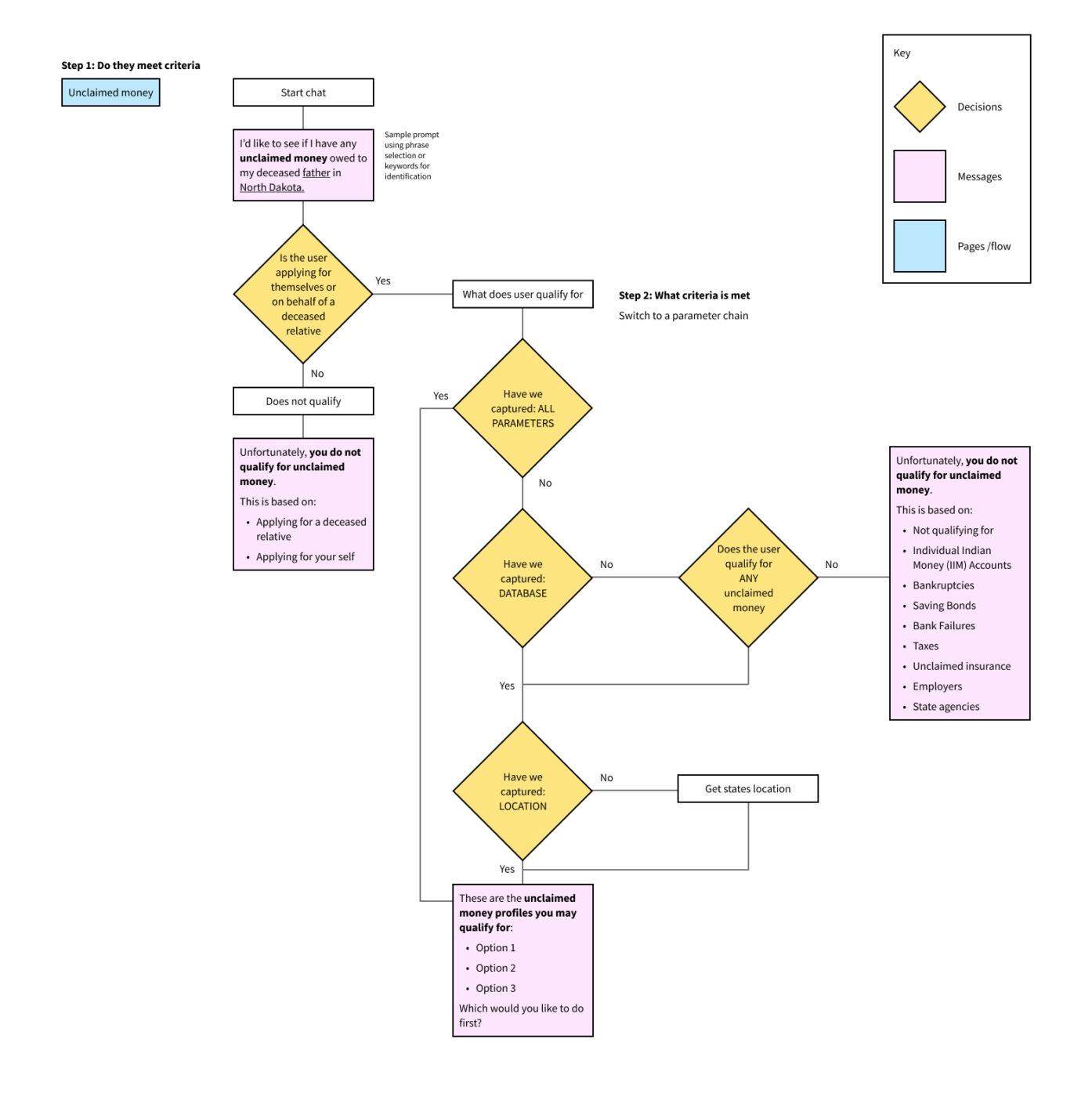

The result: We prioritized two initial flows:

- Unclaimed money lookups → High search volume, straightforward process, GSA-owned content

- GSA auctions information → Specific, factual, well-documented, GSA-specific

What we didn’t include: Financial hardship resources were considered but ultimately excluded because they live on benefits.gov rather than GSA.gov. Keeping the POC focused on GSA-owned flows allowed us to prove the concept without introducing cross-domain integration complexity.

Why this matters: I wasn’t just designing flows—I was shaping the POC scope to focus on what GSA could control and measure directly, reducing external dependencies during an already uncertain period.

Strategic decision #2:

Treating the chatbot as an agent, not a search bar

Here’s a fundamental design question: Is this a chatbot or a conversational search interface?

The difference matters:

- Search interface → You type a query, get results, done. Fast but transactional.

- Conversational agent → Back-and-forth dialogue that feels like talking to a person. Slower but more natural.

The tension: Stakeholders wanted efficiency. “People just want answers fast,” they said. And they weren’t wrong—speed matters.

But I recommended the agent approach. Here’s why:

- Trust requires conversation → Government services are high-stakes. People need to feel heard and guided, not just given a link.

- AI limitations need dialogue → If the AI doesn’t understand, a conversational flow gives users ways to clarify, rephrase, or ask follow-ups.

- Future scalability → An agent framework could eventually integrate with the contact center for warm handoffs. A search interface is a dead end.

My decision: Design conversational flows that feel human—with personality, clarifying questions, and natural language—even if individual interactions take slightly longer.

The trade-off: This required more design work. Every flow needed:

- Multiple entry points (different ways users might phrase the same question)

- Clarifying questions when intent was ambiguous

- Fallback responses for edge cases

- Exit paths when the AI couldn’t help

It also meant educating stakeholders on why longer conversations could build more trust than instant results. I had to shift the success metric from “time to answer” to “user confidence in the answer.”

Strategic decision #3:

Designing for AI limitations

Let’s be honest: AI gets things wrong. Especially in 2025, especially with government content, especially when you’re using Drupal AI and Ollama rather than cutting-edge commercial models.

The tension: Stakeholders wanted a chatbot that “just works.” But I knew from research that AI hallucinations, misunderstood queries, and off-topic requests were inevitable.

My decision: Design explicitly for failure states and user control.

Here’s what that meant in practice:

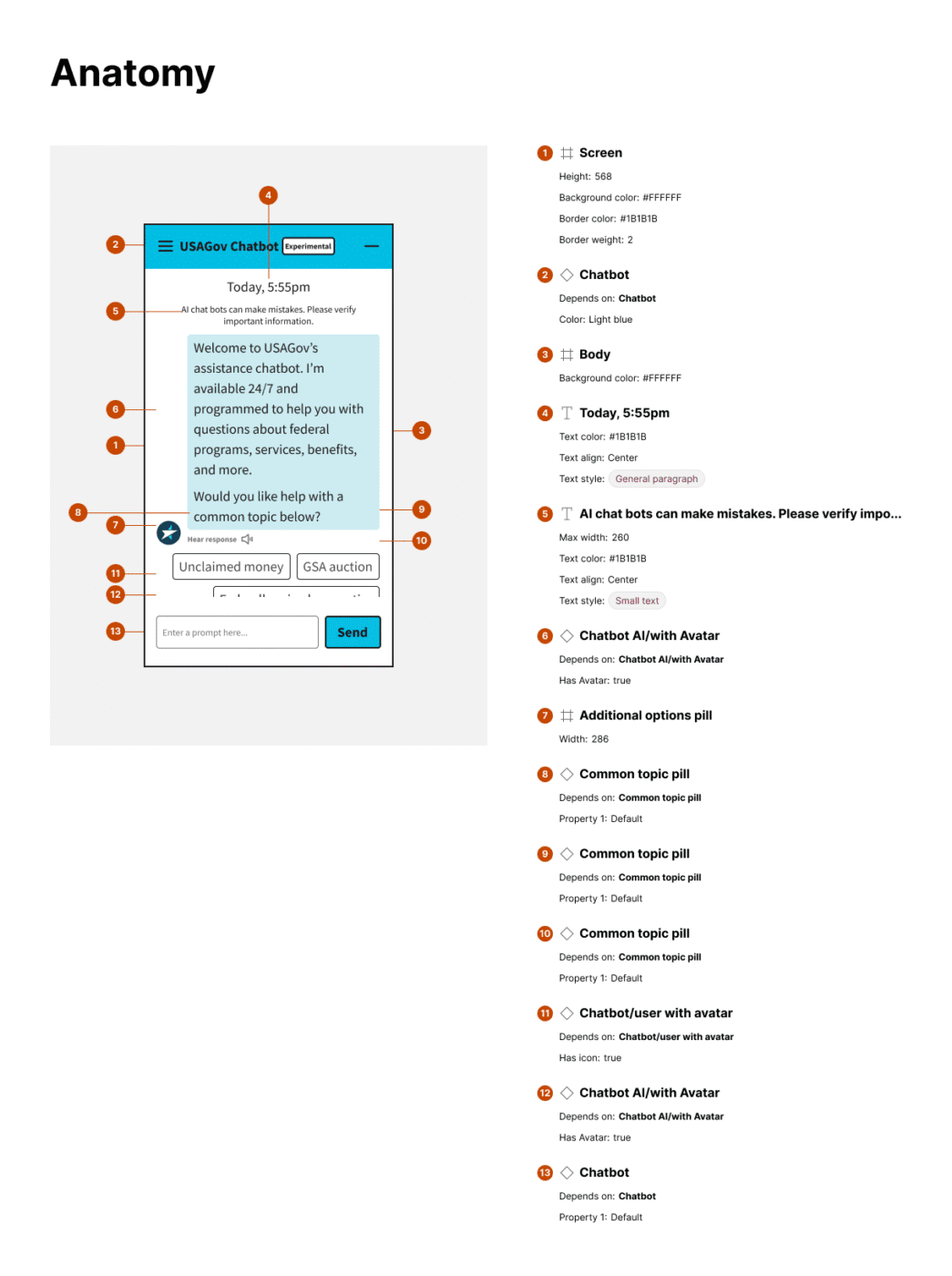

- Parameter chains as guardrails → I mapped out controllable parameters early (topic boundaries, content sources, response formats) to create visual clarity for what the AI could and couldn’t do. This wasn’t just for developers—it aligned stakeholders on realistic expectations.

- Multiple guided flows with keyword triggers → Rather than relying on pure natural language understanding, I designed structured flows that could interpret intent through keywords and phrases. This gave users “a clear path forward” even when the AI wasn’t perfect.

- Obvious exit paths → Users needed ways to revisit previous topics, escape conversation loops, or clarify intent. I treated this as a circular, user-led experience rather than a linear flow.

- Fallback responses for unsupported topics → When the AI couldn’t help, I designed graceful handoffs—either to relevant USA.gov pages or, eventually, to the contact center.

The strategic bet: By designing for limitations upfront, we’d build stakeholder confidence that this wasn’t a “magic AI” that would embarrass GSA. It was a reliable tool with clear boundaries.

Strategic decision #4:

Phased handoff strategy

Remember: This was happening during government layoffs and budget uncertainty. I was brought in on contract.

The reality: I had no idea if this team would still exist when the POC was complete—or if my contract would continue.

The tension: Do I design for long-term integration (optimistic) or short-term handoff (realistic)?

My decision: Design the POC as a standalone foundation that could either evolve or be handed off.

Here’s how I approached it:

- Built on USWDS standards → Used the U.S. Web Design System so any government designer could pick this up and understand the patterns.

- Implemented design tokens and Figma variables → Created a scalable system that could grow beyond the POC without me.

- Documented conversation design principles → Wrote clear rationale for why flows were structured the way they were, so future designers wouldn’t have to reverse-engineer decisions.

- Planned for worst-case scenario → Designed a fallback that directs users to the contact page if the chatbot couldn’t help or if the project stalled.

The philosophical shift: This changed how I thought about contract work in government. Projects aren’t just experiments—they’re foundations that need to stand alone if the team structure or contract situation changes

Navigating stakeholder uncertainty about AI

One of the hardest parts of this project wasn’t the design—it was navigating stakeholder concerns about AI itself during active layoffs.

Some stakeholders were excited. Others were skeptical. A few were actively worried about job displacement.

My approach:

- Weekly demos as trust-building → Rather than waiting for a big reveal, I showed progress every week during our contract period. This let stakeholders see the chatbot evolving and raise concerns early.

- Reframed AI as augmentation, not replacement → I consistently positioned the chatbot as “freeing up agents for complex work” rather than “reducing headcount.”

- Emphasized human control → Every design decision reinforced that humans were still in charge—setting boundaries, reviewing responses, deciding when to hand off.

- Used real contact center scenarios → I worked with the team to design flows based on actual use cases, showing stakeholders how the AI would handle real situations.

What I learned: Building stakeholder confidence is gradual work. While our contract ended before we could see long-term stakeholder evolution, the weekly demo approach helped maintain alignment and manage expectations during uncertain times.

What actually happened:

Outcomes and reality

The deliverables:

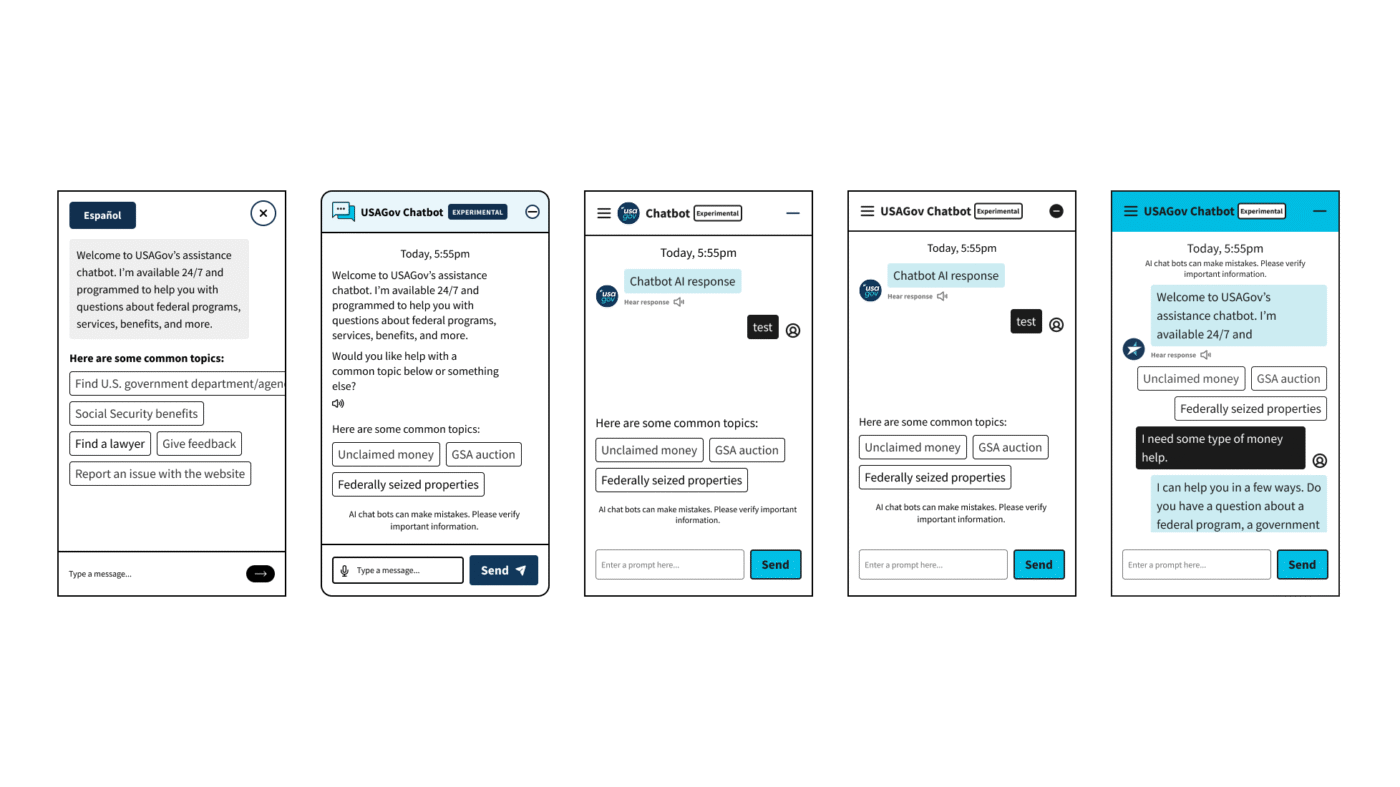

- Complete conversational flows for Unclaimed Money and GSA Auctions

- Scalable UI component library built on USWDS standards

- Design system documentation with conversation patterns and design tokens

- Technical foundation using Drupal AI and Ollama integrated with OpenAI (implemented by developers)

- Handoff-ready specifications for initial integration and sample testing

The reality:

Our contract was terminated before final delivery. The POC was ready for initial integrations and sample testing, but never went live. We didn’t receive follow-up from stakeholders after termination, and implementation metrics were never gathered.

Why I'm including this case study:

- Contract termination doesn’t diminish strategic leadership

Senior designers navigate organizational uncertainty and deliver value even when projects don’t launch as planned. The work I delivered was strategic, thorough, and handoff-ready—regardless of what happened after my contract ended. - The foundation has lasting value

The conversation design patterns, component library, and technical integration are documented and available if GSA chooses to revisit AI chatbot initiatives. Good design work survives contract changes. - The work demonstrates navigating real government constraints

Designing during RIF, managing stakeholder concerns about job displacement, and creating handoff-ready documentation when team continuity is uncertain—this is the reality of senior-level government work. - Not every senior project has a perfect ending

Demonstrating how you think, navigate complexity, and position design as strategic value matters—regardless of whether contracts continue. Senior portfolios should show the full spectrum of real-world experience, including projects that end prematurely.

This project exemplifies the reality of government contract work: budgets shift, priorities change, and contracts end. Senior leadership isn’t about perfect outcomes—it’s about delivering strategic value under uncertain conditions and building foundations that can survive beyond your immediate involvement.

What I learned about leading innovation during uncertainty

Lesson #1:

POCs require strategic framing, not just good design

Being brought in specifically to lead a POC during budget cuts meant understanding that the framing mattered as much as the design. Leadership chose this approach for lower risk and faster learning—my job was to deliver on that promise.

Lesson #2:

Design for handoff from day one

In uncertain environments—especially as a contractor—every design decision should assume someone else might inherit it. Documentation becomes strategy. USWDS standards become job security for the work, not the person.

Lesson #3:

Parameter chains are stakeholder alignment tools

Early mapping of controllable parameters wasn’t just for developers—it was a visual way to align stakeholders on realistic AI capabilities and prevent scope creep. This reduced ambiguity and built confidence during uncertain times.

Lesson #4:

Conversational design is circular, not linear

I approached the chatbot as an AI agent emphasizing conversational design principles—offering users obvious ways to revisit topics, exit loops, or clarify intent. This created a circular, user-led experience that mimics real human interaction rather than rigid Q&A.

Lesson #5:

AI limitations require proactive design, not reactive fixes

The complexity of AI variables made it difficult to establish explicit control upfront. Without real user data, I relied on informed assumptions and strategic best-bets—designing multiple guided flows with keyword triggers, fallback responses, and clear exit paths before users ever experienced confusion.

Lesson #6:

Innovation during layoffs requires empathy and transparency

The complexity of AI variables made it difficult to establish explicit control upfront. Without real user data, I relied on informed assumptions and strategic best-bets—designing multiple guided flows with keyword triggers, fallback responses, and clear exit paths before users ever experienced confusion.

Lesson #7:

Not all projects reach production, and that's okay

Contract termination before launch doesn’t mean the work lacked value. The strategic thinking, documentation, and foundation-building are what demonstrate senior capability—not whether external factors allowed the project to go live.

Reflections

This project showed me that senior-level work isn’t always about perfect launches and proven metrics. Sometimes it’s about:

- Building foundations during chaos → Creating work that can survive organizational changes and contract terminations

- Navigating stakeholder psychology → Managing concerns about AI and job displacement with transparency

- Strategic scoping → Knowing what to build vs. what to defer, especially when domain ownership matters

- Designing for handoff → Making your work resilient beyond your presence or contract

The chatbot design was solid. The conversation patterns were thoughtful. But the leadership was in how I navigated uncertainty—being brought in during layoffs, building stakeholder confidence in AI, and creating a foundation that could survive even if the contract didn’t.

Not every project gets a perfect ending with beautiful metrics and stakeholder testimonials. But every project is an opportunity to demonstrate how you think, how you navigate complexity, and how you position design as strategic value even when the path forward is unclear.

That’s what senior leadership looks like in the real world—especially in government contract work.